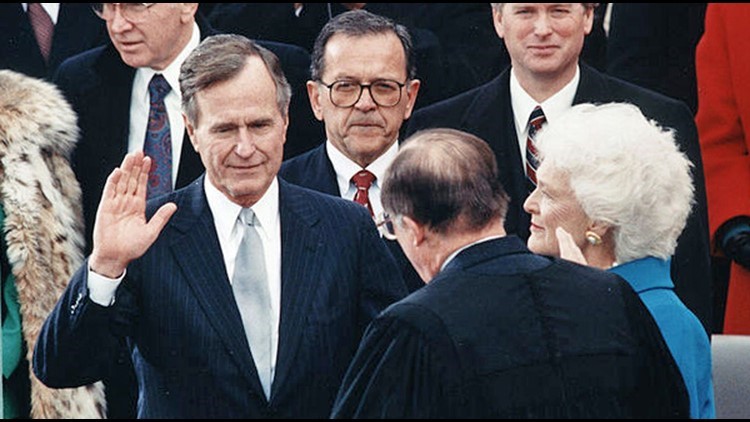

Three weeks after Independence Day in 1990, a group of White House officials, organization leaders, people with disabilities and George H.W. Bush himself gathered to celebrate another day of independence – a different kind of independence, and one that would forever change lives.

Related: NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell Issues Statement On The Passing Of President George H.W. Bush

It was July 26, 1990, when Bush passed the Americans with Disabilities Act, a law prohibiting discrimination of those with physical and intellectual disabilities. The act was arguably Bush’s most important and influential piece of legislation during his presidency.

To disabled Americans, it was their Civil Rights Act -- their declaration that they deserve the same rights as those without disabilities. To Bush, it impacted his lasting legacy.

“George Bush will be viewed by people with disabilities and their families as the Abraham Lincoln of their experience,” said Lex Frieden, a professor at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. “Abraham Lincoln, we have viewed him as the leader for people of color…George Washington, we have viewed him as the leader for (seeing) people equally…from (Bush’s) standpoint, I’ve heard him say that the ADA is the piece of domestic policy that is most significant, long-lasting and one he’s most proud of.”

Frieden, who has fought for disabled Americans’ rights since the 1970s in Houston, fostered a relationship with Bush before he became president. Frieden said he had conversations with the then-vice president about establishing equal rights for those with disabilities and the work he was doing in Houston developing programs and resources.

“(Bush) had talked about his own experiences with (loved ones) with disabilities,” Frieden said. “He pointed out he was only the vice president, but if there was anything to do to help us, he would.”

Fast forward to a summer afternoon in 1990, on the South Lawn at the White House, where President Bush declared, “Let the shameful wall of exclusion finally come down.”

Four years later, during a speech in Houston, Bush acknowledges the city’s impact on the Americans with Disabilities Act.

“Houston has had a profound effect on the ADA,” Bush said in a 1994 speech. “For decades, I’ve been proud of Houston’s vision and commitment to the issue of rights for people with disabilities.”

It was in Houston that Frieden’s efforts in establishing rights for people with disabilities began. In the 1970s, Frieden and fellow advocates protested the then-inaccessible METRO system and filed a lawsuit after The Summit was built, seeking provisions for those with disabilities in the sports arena. President Ronald Regan named Frieden the Executive Director of the National Council on Disability in 1984 where he played a role in the first drafts of the American with Disabilities Act that he and councilmembers presented to Congress.

“For me, it was a wonderful time to be in a position where I felt like I could have some impact over issues (with which) I had personal experience,” Frieden said.

Today, Frieden said the ADA’s impact extended to a personal one with Bush, as the former president spent the last several months of his life in a wheelchair. Frieden said it is elderly people with disabilities who see the impact of the ADA and what still needs to be done as those with disabilities age.

“People who are aging with disabilities…we do not have an infrastructure to support them in their own homes,” Frieden said. “My effort in the last few years is to make policymakers and the community aware of (that) because they want to be full participants (in society).”

However, it is not just people with physical disabilities who have been impacted by the Americans with Disabilities Act. Those with intellectual disabilities were impacted as well, especially in the establishment of equal employment.

“The ADA helps them know that they have rights,” said Anne Hopton-Jones, deputy director of programs at Best Buddies in Houston. “We have very intellectual, capable people willing to do the job if someone will let them do it.”

Best Buddies, an organization that helps match people with intellectual and developmental disabilities with volunteers in hopes of establishing a friendship, was founded in 1989 – a year before the ADA was passed.

“People would discriminate against someone with (intellectual and developmental disabilities),” Hopton-Jones said. “Now with the ADA in place, you’ve seen a movement in the last 10 years where it’s just now accepted on a national level.”

Both Hopton-Jones and Frieden still believe there is work to be done for those with intellectual disabilities, especially with employment. Hopton-Jones believes the next step involves employers taking more initiative to hire qualified individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. But had Bush not signed the ADA into law, she said it is unlikely employers and the general public would be aware of those who face these challenges.

“If it were not for the ADA, what would life be like?” Hopton-Jones said. “What would Best Buddies be like if people didn’t have at least a little bit of awareness? I think that’s a huge part of what he (Bush) gave to us. Twenty-five years later, we are in a good place because of it.”

It is the Bush family, she said, that has helped bring awareness to people with disabilities and the challenges they face. She said their continued involvement with the community – especially in Houston – made an “unbelievable” impact on both disabled persons and how the world will remember George H.W. Bush.

“(The ADA) is a reminder of that legacy,” Hopton-Jones said. “It’s the most important piece of legislation. I think that’s an incredible legacy to have. He brought (discrimination of disabilities) to the forefront and made sure they were accepted. That’s huge.”