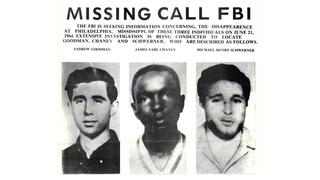

Attorney General Jim Hood announced an end to the active federal and state investigation into the 1964 killings of three civil rights workers in Mississippi.

"There's nothing else that can be done," he said in a news conference Monday. "The FBI, my office and other law enforcement agencies have spent decades chasing leads, searching for evidence and fighting for justice for the three young men who were senselessly murdered on June 21, 1964," he said. "It has been a thorough and complete investigation. I am convinced that during the last 52 years, investigators have done everything possible under the law to find those responsible and hold them accountable; however, We have determined that there is no likelihood of any additional convictions. Absent any new information presented to the FBI or my office, this case will be closed."

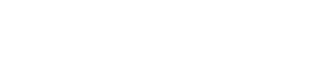

The Justice Department released a 48-page report on the case. To date, the department has closed more than 100 of the reexamined civil rights cold cases. “Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner gave their lives while struggling to advance the cause of civil rights for all," Principal Deputy Assistant Attorney General Vanita Gupta, head of the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division, said in a statement. "Though the reinvestigation into their heinous deaths has formally closed, we must all honor their legacy by forging ahead and continuing the fight to ensure that the founding promise of America is true for all of its inhabitants.”

The decision didn't surprise Schwerner's widow, Rita Bender of Seattle. "Tragically for the people of Mississippi, and for our nation, the many murders which took place over so many years, in which people of color were targeted, and those who attempted to support them became the victims of brutality as well, all deprived of basic civil rights of citizens," she said. She hopes the Justice Department report will provide an opportunity for Mississippi officials to reflect on the larger unmet needs, such as education, and "to face up to the past and for the people of Mississippi and all of our country to find the resolve to move forward."

Goodman's brother, David, of New York City, quoted author William Faulkner as saying, "The past is never dead. It's not even past."

In 2005, Hood and District Attorney Mark Duncan prosecuted Edgar Ray Killen, the only suspect ever tried for murder in the killings of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner. On the anniversary of the killings, a Neshoba County jury convicted Killen of manslaughter. He was sentenced to 60 years in prison and remains in the State Penitentiary at Parchman. Now 91, Killen has lost all of his appeals and refuses to discuss the case. Hood said he informed relatives of the victims about the decision to close the case.

"We sincerely appreciate the blood, sweat and tears of the FBI agents, Department of Justice officials, Navy Seabees, the U.S. attorney's office and local court offices that assisted in the case," he said. "The FBI agents who came into Mississippi faced threats and harassment in addition to the oppressive heat of a Mississippi summer. Despite a hostile environment, these law enforcement officers remained solely focused on locating the missing and solving this heinous crime." He thanked the Justice Department's Barry Kowalski and William Nolan as well as FBI Special Agent Jeromy Turner, who has worked on the case in recent years.

"The state of Mississippi was committed to seeing this investigation through to fruition and to moving forward," Hood said. "We should all acknowledge that our diversity is this state's greatest asset. That remarkable diversity manifests itself in the unique culture we share with the world."

There are few criminal cases in the state that have drawn more national and international headlines than the killings of Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner, which the FBI dubbed the "Mississippi Burning" investigation.

The three civil rights workers arrived in Neshoba County that day to investigate the burning of an African-American church and the beating of members in Neshoba County when Deputy Cecil Price arrested and jailed them. After 10 p.m., he released them and later helped Klansmen intercept the trio in high-speed chase down Mississippi 19. When he flashed his red lights, the trio pulled over their station wagon.

Taken to remote Rock Cut Road, they were killed by Klansmen and their bodies buried 15 feet beneath an earthen dam.

Forty-four days later, a tip to the FBI led to the grisly discovery of their bodies.

In 1967, Price was among seven convicted on federal conspiracy charges. Eleven others walked away, including Killen. Hood said there were two suspects still living, James "Pete" Harris and Jimmy Lee Townsend, but there is not enough evidence to pursue cases against them. According to testimony in the 1967 federal trial, Harris made telephone calls to help gather Klansmen to beat and eventually kill the civil rights workers. Townsend, a teenager at the time, was reportedly in one of the cars in that high-speed chase, but stayed with the car when it broke down.

According to the Justice Department's report, authorities tried to get Townsend to testify against Harris and Olen Burrage, who owned the property where the three civil rights workers were buried, but Townsend maintained he knew nothing about the killings.

Klansman James Jordan, who pleaded guilty to federal conspiracy charges, testified that Harris received authorization from then-Imperial Wizard Sam Bowers to kill Schwerner. The report noted that no evidence showed that Harris passed on that instruction to anyone else. A former Klansman from Meridian who previously implicated Harris has now retracted that information, according to the report. Much has been done to memorialize the three slain civil rights workers. Mississippi 19 in Neshoba County now bears their names, and a historical marker recognizes their deaths.

In 2011, the Jackson FBI office was named after the slain trio and Roy K. Moore, the FBI agent who opened the office in 1964 and headed the investigation. In 2014, President Barack Obama gave the highest civilian honor to the three slain civil rights activists whose work with others helped pave the way for him to become the nation's first African-American president. He handed the Presidential Medal of Freedom to the families of Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner.

When Freedom Summer came, these three young men "refused to sit on the sidelines," Obama said.

Their killings "shook the conscience of the nation," he said. "It took 44 days to find their bodies and 41 years to prosecute their killings."

He said the medals are meant not to honor their deaths but "to honor how they lived."