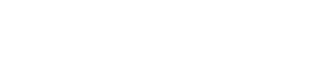

Researchers have completed a breakthrough study that used GPS collars to track black bears in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The results are shattering some long-held beliefs about where the animals travel for food. It may also force entire counties to rethink their bear-proofing policies.

"We always thought there were two kinds of bears. You had 'front-country bears' that show up in campgrounds or communities along the boundary of the park. But we thought around 95 percent of bears in the park were 'back-country bears' that went about their business, living in the woods, with very little contact with humans. This research shows that was an absolute fallacy," said Joe Clark with the USGS.

Clark supervised a research project by University of Tennessee graduate student Jessica Braunstein. In 2015, the project placed GPS collars on 27 conflict-bears and tracked them for a year. Then the study collared and tracked a group of well-behaved back-country bears to compare the differences in their behavior.

"The GPS technology and these collars gave us a chance to do something nobody had done before. In the past with the old technology, it would be really easy to just lose track of those animals," said Braunstein. "To actually see with the GPS how far out all the bears go out of the park, I had no idea. I don't think I realized it was as much of a problem as it was."

REDEFINING "BEAR COUNTRY"

Braunstein's project makes a myth of "front-country" and "back-country" labels for bears. Of more than 50 bears tracked, almost all of the animals traveled outside the national park to find food. That was the case if the bear was collared while seeking food in a parking lot or minding its business deep in the woods

"Especially with male bears, 93 percent left the park boundary at some point. We knew males travel farther than females because they go out looking for a mate. But even 60 percent of the females left the park," said Braunstein. "The food-conditioned bears had the smallest home-ranges. Because they locked in on trash and other human sources of food, they didn't have to travel as far."

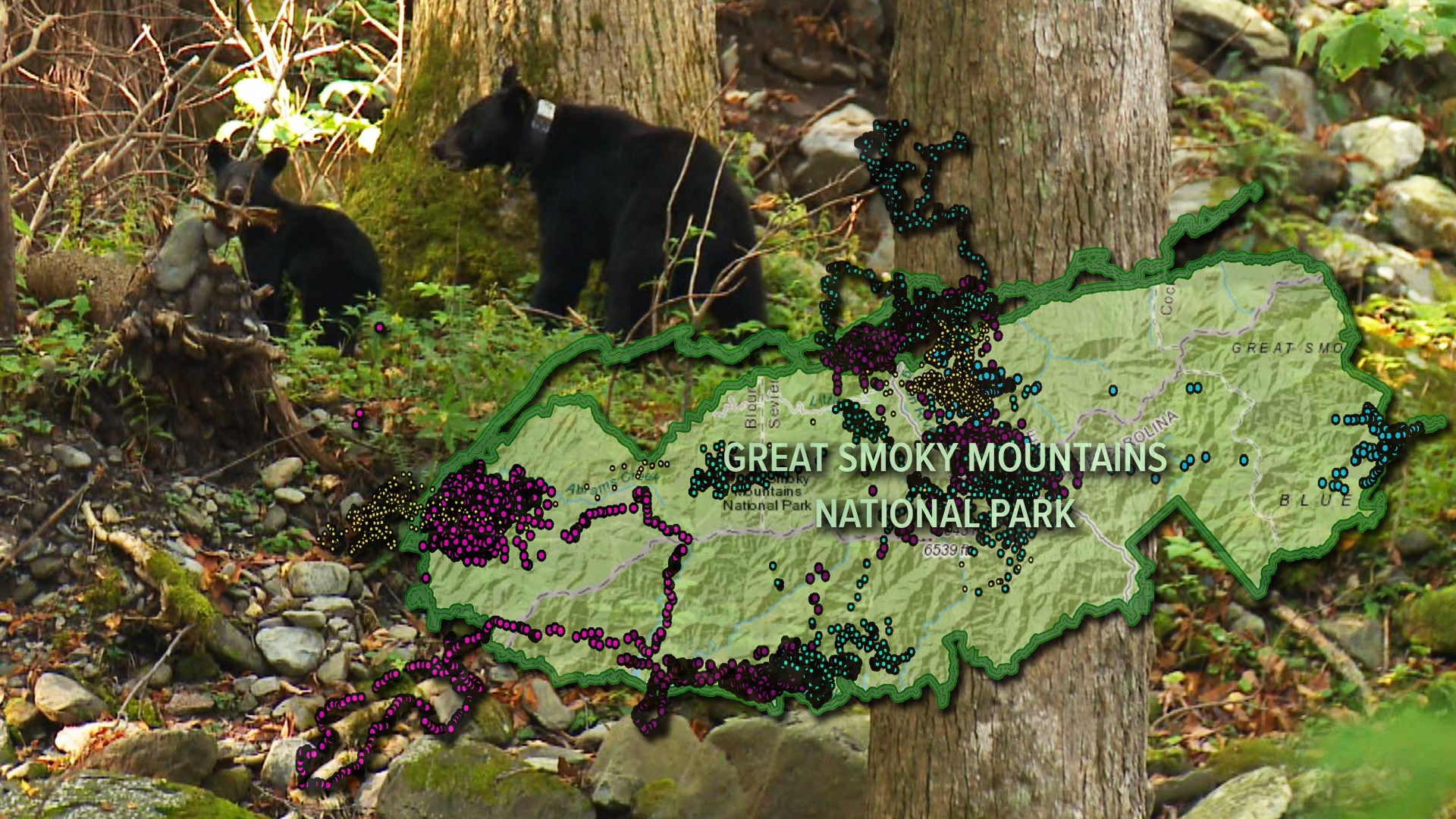

The GPS collar plots the bear's location every two hours when inside the national park boundary. When the collar leaves the Smokies, the rate increases to every 20 minutes to gather better information on where bears travel in communities.

"I think what was surprising to me was how far out in to the communities these bears are going. They go all the way across the park from one side to the other. And they go in-and-out of the park at every corner of the park," said Bill Stiver, GSMNP supervisory biologist.

"Bears are leaving the park at all sides of the boundary. It's not just the Gatlinburg area. If he [a bear] is not getting food in Gatlinburg, it doesn't mean he's not going to go to Cataloochee, or Cosby, or go to Townsend," said Braunstein. "The bears you see on one side of the park can be the same bears you see on the other side."

FOOD ODYSSEYS

Male bears showed a larger overall range than females. The GPS collars demonstrated how some bears had routines of traveling great distances to reach familiar areas.

"We had a 5-year-old male bear that was in Cataloochee. It would lock in there for a couple of months, then go straight across to the area between Gatlinburg and Mt. LeConte. He focused on those areas and just went back and forth," said Braunstein.

Even female bears with small cubs traveled great distances in search of food, especially during years when trees did not produce as many acorns and hard mast.

"We would have never seen this with old technology," said Stiver. "We collared a bear at the Grotto Falls parking area [on Roaring Fork]. She had two cubs with her. Later she showed up on Hyatt Lane in Cades Cove. I would have never guessed a female bear from Grotto Falls would be in Cades Cove. Then she kept going west all the way to the Foothills Wildlife Management Area [outside the western edge of the park]. That's more than 30 miles away from where we collared her. Then in November, she made a beeline all the way back to Grotto Falls where she denned. The next three years, she stayed there in her home-range around Grotto Falls."

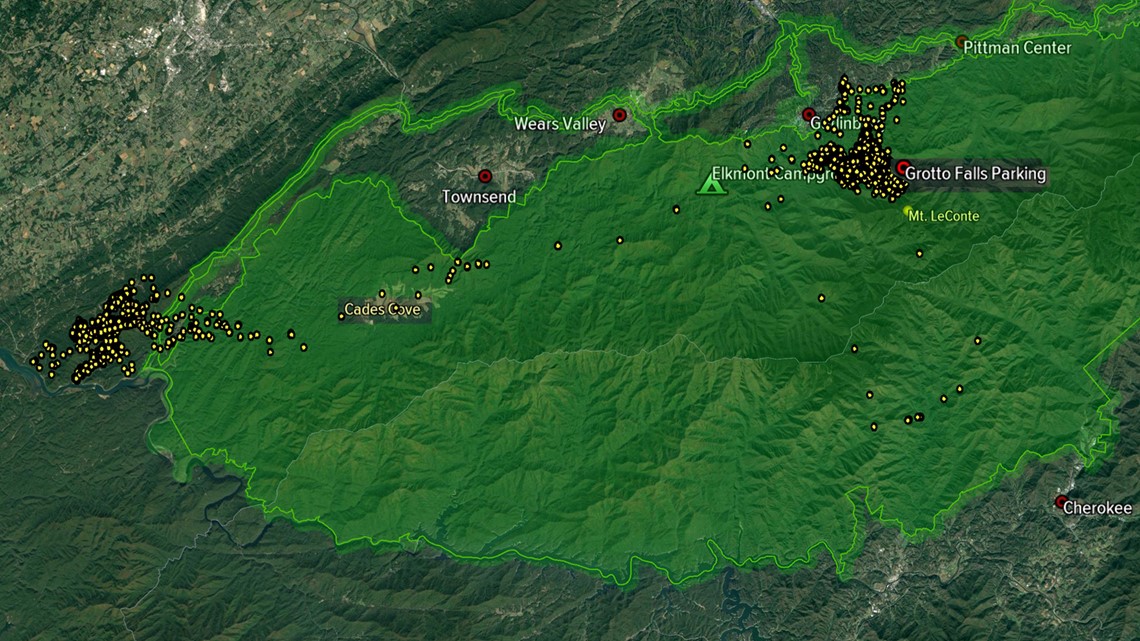

In another example from 2015, a female with two cubs took a meandering 36-mile path from Elkmont to Sevierville with her small cubs in just a few days.

"We collared the bear in the Elkmont campground. She and her cubs went outside the park, took off up to Pigeon Forge, came back down the Spur to Gatlinburg, looped over near Pittman Center, then went up to Walters State Community College [Sevier campus]. She hung out there in a stand of oak trees beside the soccer fields. Then she went all through downtown Sevierville. And she had cubs with her the whole time," said Stiver.

BEHIND THE CURVE

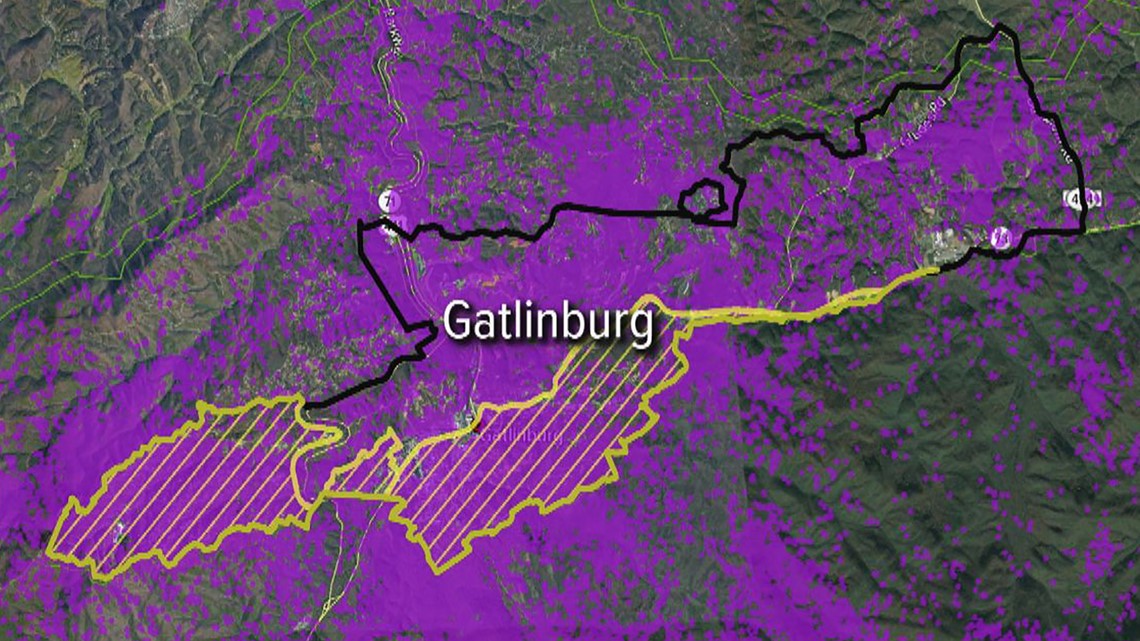

The scientists were interested to see how bears behaved in areas that are bear-proofed in Gatlinburg. The city borders the park and took a proactive step in 2000 by creating bear ordinance zones that require animal-resistant trash cans.

"Back then, the thought process was if we make a boundary that is bear-proofed, maybe the bears in the park wouldn't keep going beyond that area if they didn't find food or garbage," said Stiver. "The study shows they go right through that ordinance zone and far beyond it, then come back inside the park."

Stiver says the ordinance zone was a positive step, but a lot has changed since it was created.

"We have a lot more bears, a lot more visitors, and a lot more people living in the counties around the park. In 1992, we had between 400 and 600 bears in the park. Now we have 1,600. The amount of visitors in the park in a year has gone from 8.9 million to 11.3 million. And the population in Sevier County alone has gone from around 55,000 to 97,000," said Stiver.

Park biologist Ryan Williamson spends much of his time trying to keep bears and visitors safe from each other. For years, he has trapped conflict-bears and relocated them to isolated areas of the park.

"The GPS collar technology has showed us there is no 'farther and deeper into the woods' to take bears away from people. The park is 800 square miles, but that's not big enough for the territory these bears cover," said Williamson. "These are not just the park's bears. Bears are expanding and we are behind the curve on bear-proofing in the areas around the park. I know when that bear starts showing up around people and around cars and around trash, that bear's life span is greatly decreased. The black bear is one of those iconic things we want to pass on and protect it for future generations to enjoy." "

"The national park is certainly not an island. The park is huge, but it is not big enough for a self-contained population of bears," said Clark. "There are very few bears who are not impacted by what goes on outside the park."

EXPANDING BEARWISE EFFORTS

Williamson said he'll remember many things about the GPS study. In one case, a collared bear died when it fell out of a tree.

"I have had countless people see bears up in the trees and ask if they ever fall. I assumed it might happen, but never had proof until this study when we found a bear fell out of a tree near Laurel Falls," said Williamson.

By far, Williamson says the greatest thing he takes away from the research is the need to broaden the perception of who needs to bear-proof their homes.

"I would personally love to see entire counties commit to bear-proofing. We need to step back and look at this on a much bigger level than just part of a city, because that zone in part of Gatlinburg is the only place with any kind of ordinance. These bears go to Pigeon Forge and Sevierville. They go to towns and neighborhoods along the entire boundary of the park. The counties and communities need to come together. And we need to educate people who may have never thought they needed to bear-proof their homes," said Williamson.

"The next step is to take this information and show it to the different municipalities and governments. We have a bear task force that has been in place a number of years with TWRA, the city of Gatlinburg, and the National Park Service. I'll show them the same maps I'm showing you. We made a lot of progress in the 1990s and early-2000s. Now it is time to take another look to help protect bears and people," said Stiver. "We have to do the fundamental thing and that is manage our garbage."

The GPS-collar research was funded by the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency (TWRA), the USGS, the National Park Service, Friends of the Smokies, and UT Forestry, Wildlife and Fisheries.

Stiver says TWRA is also working heavily with 13 other states on the BearWise program. The program's BearWise.org website helps educate people how to live safely in areas with bears, ensuring all states provide consistent messages to people. The program also grades education efforts and bear-proofing policies to designate communities as BearWise.