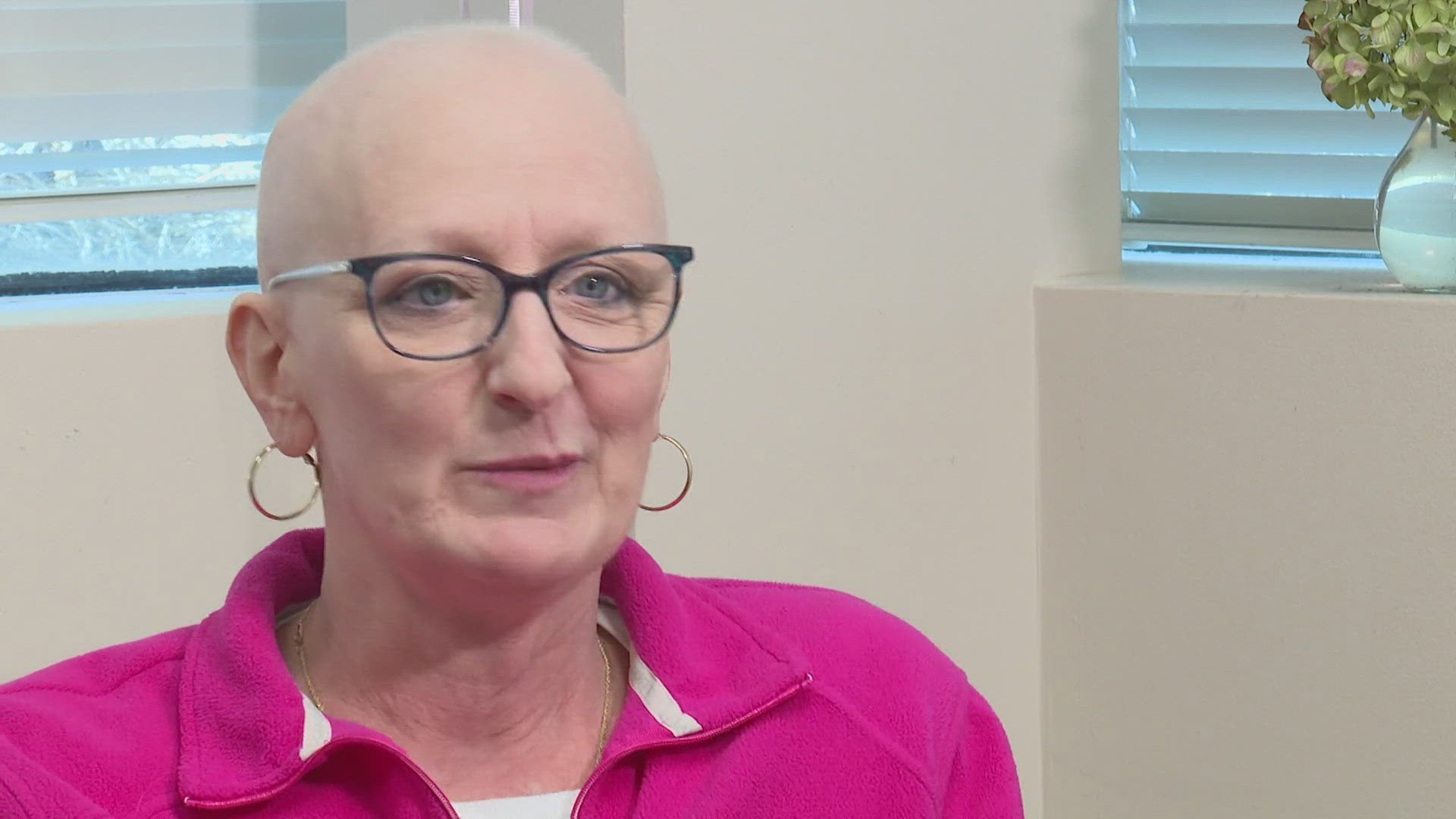

GREENSBORO, N.C. — Kathy Richardson, MD, can picture the face of every one in eight who has become a statistic, caught in the ruthless realm of breast cancer.

“I think all women feel a bit like, ‘It’s coming for me.’ I just sit here and think of all the women through the years, you know, patients and friends…women who survived and women who haven’t,” she reflected.

As a board-certified obstetric gynecologist (OB-GYN) at Greensboro OBGYN Associates, Richardson is a first line of defense against breast cancer, checking breasts during annual exams and assessing risk.

MONITORING BREAST HEALTH

“I do want people to understand that no woman makes breast cancer happen to herself. Breast cancer is so multifactorial. There are so many things that trigger cells to turn on and mutations to turn on that you cannot attribute it to one thing,” she explained.

Research shows nutrition, exercise and weight can influence the likelihood of a diagnosis, though the foretelling factor is family.

“I had a maternal aunt who died in her early 60s of breast cancer, and then my sister was diagnosed when she was 40 years old,” Richardson said.

Her family story is why she pesters her patients – and herself – to get annual mammograms.

FROM DOCTOR TO PATIENT

“So luckily, we have a mammography unit in our office (at Greensboro OBGYN Associates)…doctors are the worst patients, admittedly,” she sighed.

She said thankfully, colleagues hold one another accountable, and mammogram technologist Edna Waddell keeps track of the physicians’ check-up schedules.

“I’m like, ‘You’re due for your mammogram. Get down this hallway. I will get you in,’” Waddell recalled telling Richardson one day this spring.

When Waddell did Richardson’s scan, she suspected something was wrong.

“I saw it (a mass) right away and knew she was gonna get that letter that came back and says, ‘You need to follow up.’ It looked bad,’” Waddell remembered.

TRIPLE NEGATIVE THREAT

The diagnosis – as confirmed by a radiologist and later oncologist—was Triple Negative Breast Cancer, which spreads faster and carries a worse prognosis than other types of estrogen-positive breast cancer.

“It doesn't have any real great receptors on the outside of the cancer cells that you can easily attack. So, you're doing kind of the shotgun blast of chemotherapy, hitting it with everything,” she explained.

Richardson thought she was Stage 1, but her oncologist later determined she was an early Stage 2.

“If you get into a Stage 2 or Stage 3, it’s like five-year survival (the standard measurement) at 60 percent. So, the further into it you go, the harder it is to completely clear it from your body,” she said.

She was heading out on a trip to see her daughter in Spain but knew she had no time to waste, so she broke the news to her family and the dozens of pregnant patients in her care at the time.

Then, she had two surgeries – a lumpectomy and reexcision, endured 13 rounds of chemotherapy and began immunotherapy, each step providing painful perspective of others who have walked the same journey.

LONELY BUT NOT ALONE

“I think I was prepared for a lot of things. I wasn’t really prepared for the loneliness of it, and it’s not like I didn’t have support… When you’re in it, nobody else can do it with you…and all of a sudden, you’re removed from this life that has been your life for so long, and it’s not anymore,” she reflected.

In battling tough moments day to day, she has found strength in accepting support and finding moments of laughter. She often touches her now-bare scalp, where locks of natural red hair once lay, feeling her power to spread awareness about early detection.

“I just want people to know it’s all right. And, I mean, yeah, does my head get cold? For sure. I understand my poor, bald daddy now,” she smiled.

With a goal of going back to work in early January, she vows to share her story.

“I want them to feel they’re not alone, you know? You’re not alone…”

It is a message her tight-knit ‘Team Kathy’ community takes to heart, knowing sometimes hope…is just what the doctor ordered.

WHEN TO SCREEN

Over the next two months, Richardson will begin radiation in her journey to remission.

She and the Society of Breast Imaging recommend women start annual mammograms at age 40 or 10 years before the age at which a close family member got breast cancer (for example, if a mother received a diagnosis at age 45, her daughter should begin mammograms at age 35).

Women with dense breasts might need additional screenings every year, because dense tissue often masks signs breast cancer on mammograms.

If lack of insurance is a barrier to a breast exam, there are resources, like the Cone Health Mammography Scholarship Fund.