Bob Solomon was counting the hours until he could start counting sheep in the new queen-size bed he’d ordered from Amazon. “I’d cleared out the old mattress and box spring, and hand-waxed the bedroom’s parquet floor to prepare for the delivery,” says Solomon, a CR member and retired professor from Alberta, Canada. But on the day the bed was guaranteed to be delivered, it never showed up. At least not at his address. “From outside my house, I could see the box sitting at a neighbor’s, about a block away,” he says.

It was too heavy for Solomon to carry and too large to fit into his car, so he reached out to the shipping company, Purolator, by phone and email. “They kept insisting that their GPS coordinates showed the box was at my home, and that if I just stepped outside I would see it,” he recalls. “I told them I was standing outside and it wasn’t there. But they ignored me.”

More than 24 hours, 12 emails, and many phone calls later, the shipping company admitted its mistake. But even then the company said delivering the bed would take three more days because it had to do a mandatory warehouse search first. “I told them, ‘This is crazy! This is illogical!’” Solomon says. “I felt so frustrated and ignored and mistreated that I canceled the order even though I really wanted the bed.” Amazon ultimately saved the day by delivering a new bed and extending Solomon’s Prime membership for his trouble. He was sleeping in his new bed two days later.

(Purolator told CR that it regrets the error and is reviewing its procedures to prevent this type of miscommunication in the future.)

Consumers have been frustrated by dismissive, unfair, and otherwise unacceptable customer service since the dawn of commerce. One of the earliest recorded complaints was lodged in 1750 B.C. by a Babylonian demanding a refund from a merchant who sent him copper ingots of inferior quality. “What do you take me for, that you treat somebody like me with such contempt?” the unhappy customer asked in an entreaty that was engraved into a clay tablet but would not be out of place in one of today’s online product reviews.

People eventually put their complaints on paper, then moved on to the telephone and email, but little else changed in the intervening 3,000 years. Now, however, social media and other forms of technology are beginning to radically reshape the customer service landscape, giving consumers powerful new tools to solve problems and make themselves heard.

Consider the experience of Jean-Luc Bourdon, a financial planner in Santa Barbara, Calif. When the Hertz car he’d reserved at the airport in Tahiti wasn’t available and he was forced to rent from another company, he called Hertz customer service and spoke to an agent who said the company would get back to him within days. Not satisfied with that response, Bourdon tweeted a message to the Hertz social media team. It responded immediately and referred him to another department, which ultimately refunded the amount he requested and awarded him enough points for a complimentary rental. (A Hertz spokesperson said that all of the company’s customer service agents are empowered to resolve any issue a customer may face.)

“My instinct is to call first because it can be a lot more efficient than back-and-forth messages over social media,” Bourdon says. “But when I really run into frustration, I find social media to be the best remedy.”

Apart from social media, companies are increasingly using other technologies to interact with customers. While some of these, such as web chats, have the potential to improve service, others are raising concerns about privacy and fairness, because they rely on data that may be inaccurate. (See “Paying With Our Privacy: When Technology Meets Customer Service,” below.) With so many ways to reach out to companies—from calling to chatting to email to posting on Facebook and Twitter—it pays to know how they can work for you—and potentially against you.

Decades of Discontent

Consumers have had it. More than half of Americans report that they’ve had a problem with a product or service in the past year. Of those, more than half said they were extremely or very upset by the experience, and a third reported feeling anxious, betrayed, or sad about it, according to the 2017 Customer Rage Study, conducted biannually by the consulting firm Customer Care Measurement & Consulting (CCMC) and the W.P. Carey School of Business at Arizona State University. Moreover, the study found that only 18 percent of people who’ve complained about problems were completely satisfied with the actions the company took to resolve them. That sorry satisfaction rate isn’t something new: It’s actually somewhat lower than the 22 percent of respondents who reported being completely satisfied 41 years ago.

Still, while the problems you might expect—waiting endlessly on hold, dealing with faulty voice recognition, jumping through hoops to cancel a service—are the source of many woes, experts say much of our present dissatisfaction stems from a complicated confluence of factors.

“Twenty years ago, a faucet was a chunk of metal that you expected would last 30 years,” says John Goodman, vice chairman of CCMC and the author of two books on customer service. “Now, you can talk to your faucet or wave your hand at it to get it to work. There’s technology in everything we buy.”

Many products today are interconnected, which can make it difficult to know where to turn when there’s a problem, says Kate Leggett, an analyst who covers customer service trends at the research and advisory firm Forrester Research. “You have to ask yourself if the problem is with the internet, the router, the product itself, or a combination of all three,” she says.

There’s also been a shift to self-service, because the basic questions we used to call about are easily answered by referring to the FAQ section of a company’s website or by watching a YouTube video. (An unofficial video on how to clean the Dyson V6 cordless stick vacuum, for instance, has 2.9 million views.)

“Now, by the time consumers contact customer service, they’ve exhausted the many ways available to find an answer,” Goodman says. “That means they’re likely dealing with a complex issue that by its nature is not easily solved.”

Experts say our discontent also may be linked in part to a handful of companies that have raised the customer service bar so high that we’ve come to expect a similar level of care from everyone we do business with. “Consumer expectations have risen because of the great personalized experiences companies like Netflix, Amazon, and Uber are delivering,” Leggett says. “So we’re no longer comparing the customer service of, say, one financial institution to another. We’re comparing the quality of service we get from a financial institution to the ease and simplicity of returning a product from Amazon.”

When to Tweet, Post, or Chat

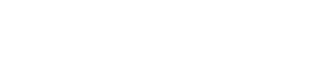

When a company lets us down, most consumers—particularly those 35 and older—turn to the phone, according to an annual survey by the information technology firm Dimension Data. In an informal poll conducted by CR on Facebook and Twitter, a large majority of respondents said they preferred to contact a company by phone when they had a complaint, while only a small fraction said social media was their first choice. “When you’re really angry, you want to talk to someone and convey your rage,” Goodman says. “On the phone, I can also tell from the agent’s voice if he’s really going to help me or not. That doesn’t come through via email or other nonverbal channels.”

Of course, calling can come with its own frustrations, including phone trees, an eternity spent on hold, and being pingponged from person to person. The Customer Rage Study found that people are referred to a different contact 75 percent of the time they reach out to a company to complain, with customer satisfaction dropping each time.

In the CR poll, an online chat was the second most popular way to reach a company, after the phone. It’s true that response times, especially for basic questions, may be much quicker using a web chat than contacting a company by phone or email, but none of the CR members or customer service experts we talked with said that chatting was any more effective.

Social media lagged far behind phone calls, email, and web chats for a vast majority of people in CR’s informal poll and the Dimension Data report. But it appears to be a powerful secret weapon when it comes to customer service, many experts and consumers say.

“Smart consumers know that if they contact a company on Twitter or Facebook, they’ll get a better response and a faster response than they will if they call customer service,” says Sunil Gupta, co-chair of the Driving Digital Strategy executive program at Harvard Business School. “No one else knows when you call a company with a problem, but on social media a lot of people see the complaint, which is exactly what companies are worried about. It certainly is a way to get a company’s attention.”