‘LET US DIE’ | The untold story of a 13-year-old girl and Russian war crimes in the final days of World War II

An old desk from an estate sale and a chance meeting with a Hollywood star unlocked an untold story from World War II.

Purchasing a desk he did not want DALLAS

Serendipity is defined as an unplanned fortunate discovery. That term is behind almost every development in the tale you’re about to read.

As a young man, just out of college in the late 1980s, Tim Mallad needed some furniture, so he purchased a dresser at an estate sale for $25. But by the time he went back to pick it up, the dresser was gone.

The manager of the estate sale apparently sold it to someone else. What’s worse, he also refused to refund the $25 that Tim paid. But, as a consolation, the estate sale manager offered Tim an old, beaten-up desk with a drop front over in the corner that no one apparently wanted.

Tim reluctantly took it. Carrying it upstairs to his place, he realized the mail cubby was rattling noticeably.

Just before he was about to drill a screw into it, to secure the mail slots into place, Tim tugged on it and to his surprise, out came a drawer.

Inside was an old British Passport, black and white photographs, a letter from Tel Aviv, international air mail from the 1950s, and a collection of fragile letters that were written in German at the end of World War II.

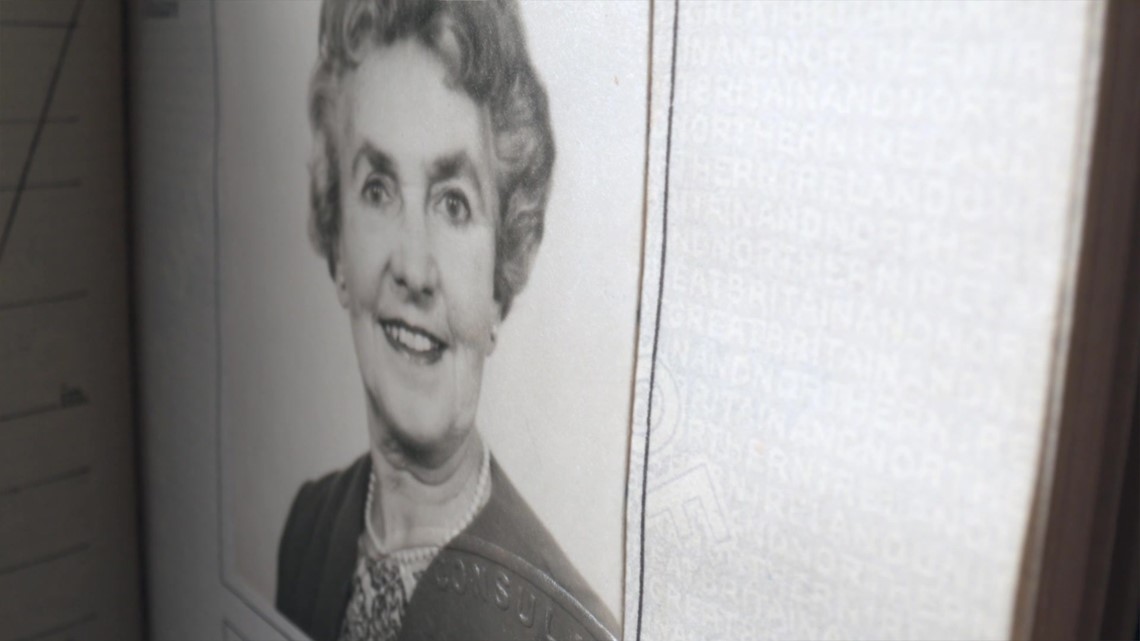

Tim Mallad knew the desk once belonged to a woman named Helen Sebba. It was her picture in the U.K. passport. Mrs. Sebba, a widow, also used to live at The Whittier, the senior living complex in Detroit, where Tim was working.

That letter from Israel – dated July 1975 – detailed the reparations from the German government to which Mrs. Sebba was entitled. Another handwritten note mentioned the Sebba family’s escape from the Nazis after Kristallnacht in 1938. Judging by it all, Tim deduced that Mrs. Sebba must have been Jewish.

But what did it all mean? Those fragile letters he found in the hidden drawer remained mysterious to him. They were written in an old German script that few younger Germans can read.

Over the years, Tim asked people who spoke German to translate the fragile ones for him. Each person came back in tears – telling Tim they were personal in nature, involved a child and that he was just better off not knowing.

Unable to figure out what they said, and realizing their importance, Tim tucked those fragile letters back inside that secret drawer.

He didn’t know it at the time, but this discovery would consume him for years

Chance meeting with a Hollywood star MALIBU, CALIFORNIA

In 2014, the story takes another serendipitous turn.

On a flight from Dallas / Fort Worth to Nashville one morning, Tim Mallad had an empty seat open next to him. Just before the cabin crew closed the forward boarding door, a woman walked aboard.

As she struggled to put her bag in the overhead compartment, she said something about having short arms, Tim said.

“It was an English voice,” he recalled. “I knew that I had heard it somewhere before.”

Tim Mallad helped her stash her luggage and the two began casually talking as the jet took off for the 90-minute flight.

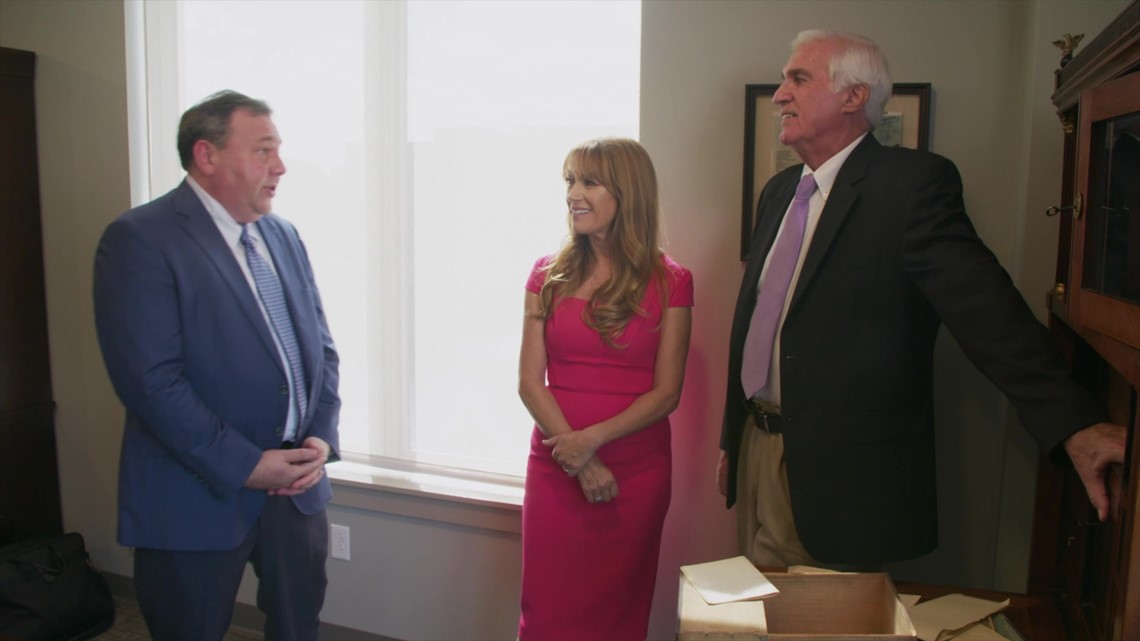

Turns out, it was the actress, Jane Seymour.

As she and Tim talked about life and their own journeys through life, Tim mentioned the German letters he found in that old desk 25 years earlier.

“I was crazy enough to say ‘Hey I make movies about this kind of stuff. Who knows what’s in those letters? You should find out. It was a little audacious of me,” Seymour said.

At her urging from that chance meeting aboard a flight, Tim decided to finally pull those fragile letters back out and hire a professional translator to take a look at them.

“If they were important enough to be hidden away, they’re important enough to be translated,” he recalled her saying.

But Tim was not prepared for what they said.

“May 1st [1945] was a particularly bad day. Continuously the Soviets entered, looted, and took possession of the young girls,” the letters stated.

A refugee named Olga Holzapfel penned the letters to Mrs. Sebba and explained how conquering Russian soldiers raped German women and German girls as they made their way toward Berlin in April and May 1945.

The letters also reveal how thousands of German families then took their own lives in the final weeks of the war. These were not Nazis. They were civilians. Families. Exhausted by war and in fear of an uncertain future.

“I was stunned because this was part of the war I didn’t know about,” said Seymour.

“I understand why they were hidden. It’s nothing you want to hold in your hand after you read it. But it was so important that I knew it had to be saved,” Tim explained

The 13-year-old girl 'begged her father, 'let us die'' NEUSTRELITZ, GERMANY

But the letters Olga Holzapfel wrote to Mrs. Sebba revealed something else, something very personal.

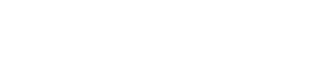

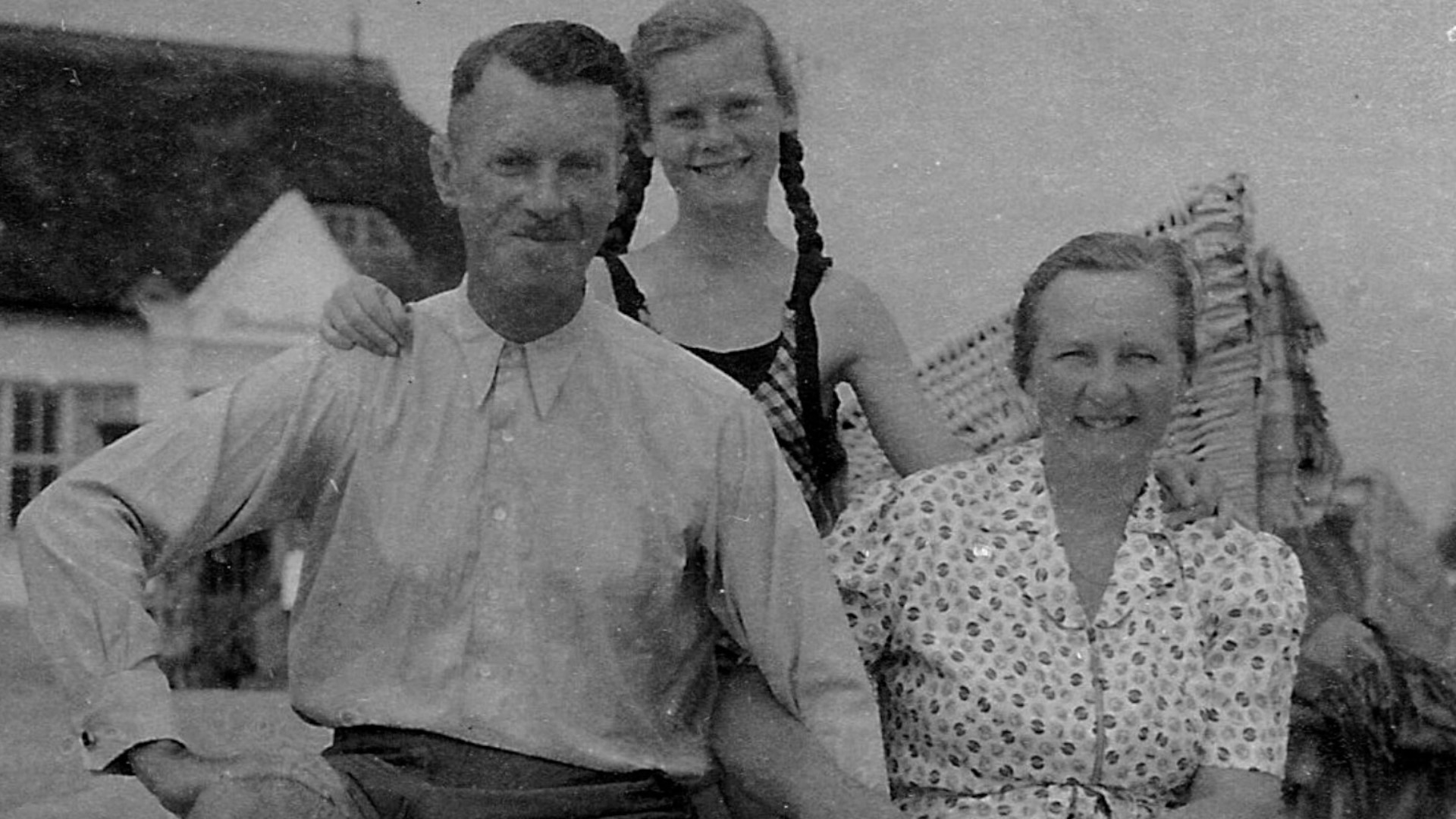

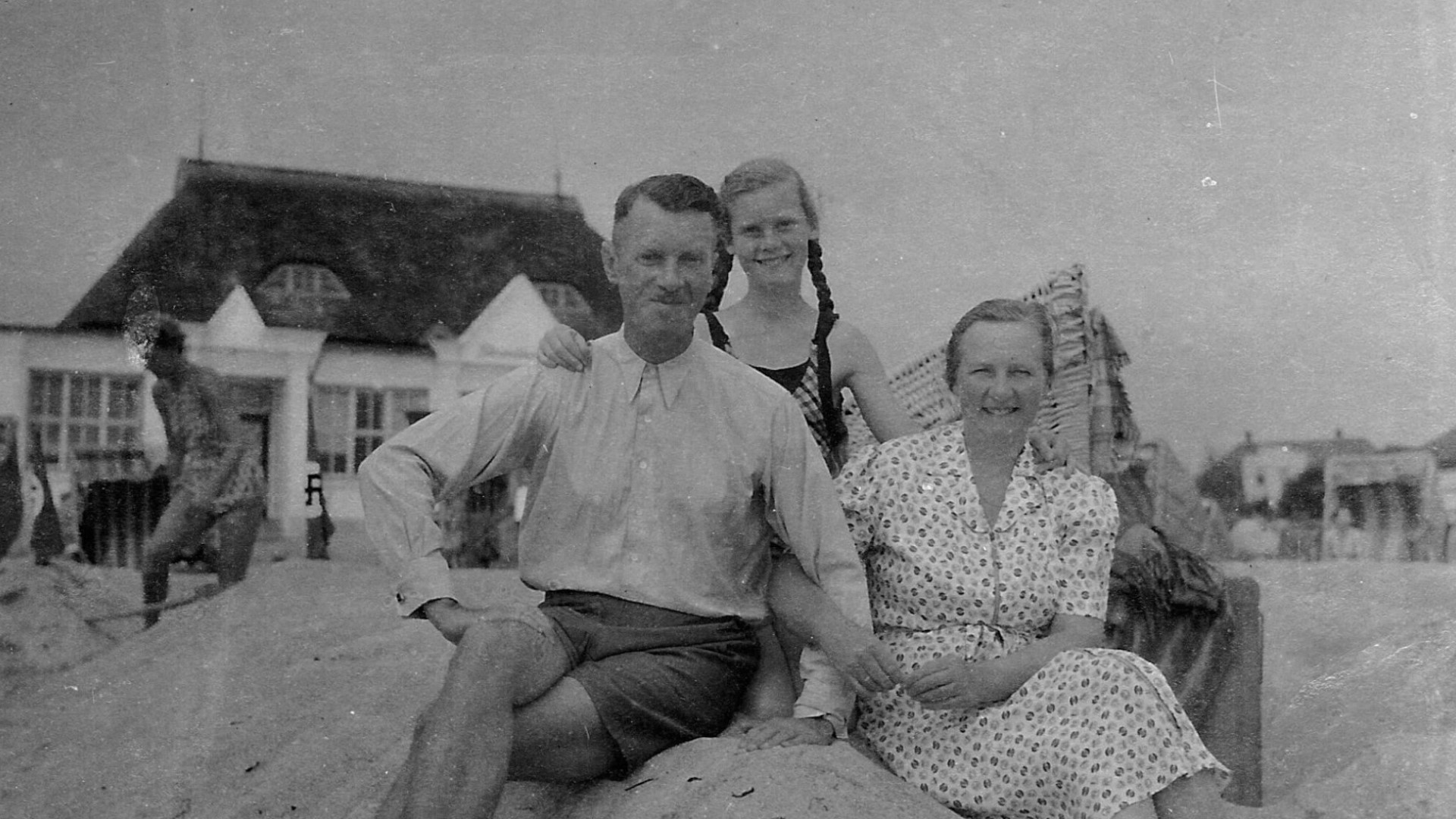

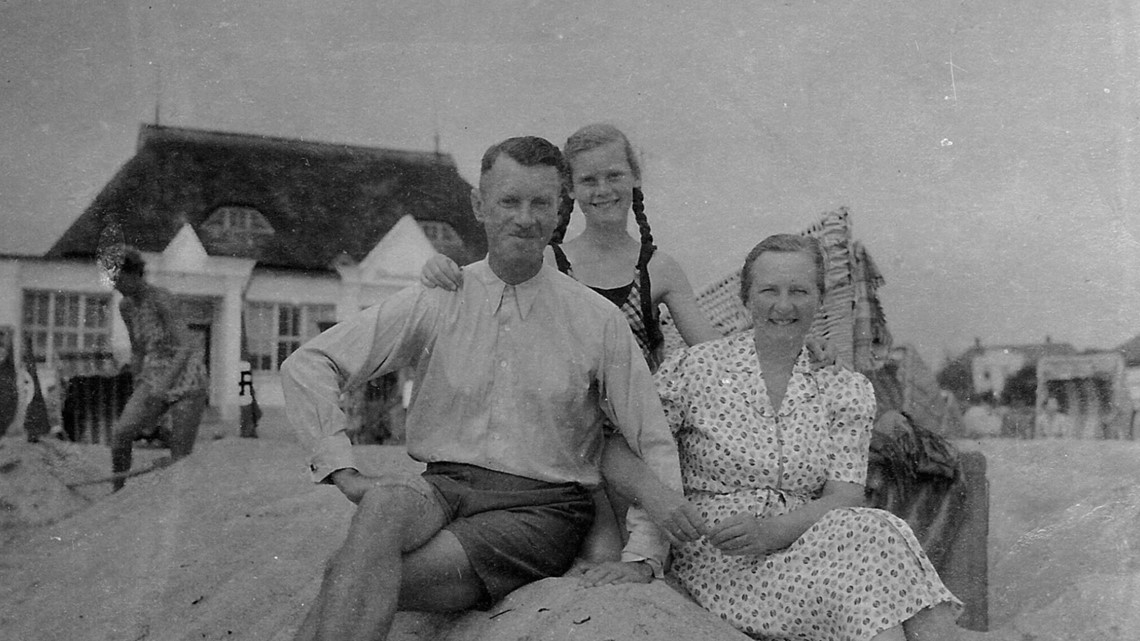

In heartbreaking detail, the fragile stationery explains the tragic final moments of Helen Sebba’s brother, Willy Weiss, his wife Dora and their 13-year-old daughter, Ulla.

“When once again, another three fellows entered and tried to drag Ulla away, they grabbed in despair the one thing they had always planned; potassium cyanide,” Ms. Holzapfel wrote.

Ulla begged her father “Let Us die,” according to the letters.

Ms. Holzapfel was a refugee in her 60s who fled fighting in Konigsberg and sought shelter with the Weiss’.

As a witness to their suicides, she wanted to tell Willy’s sister, Helen Sebba, what happened to him. The Red Cross was still working its way across Europe documenting deaths and officially telling next-of-kin.

“Have you ever been sucker punched?” Tim asked. “It hurt your heart to read the letters.”

In the final week of the war, the Weiss’ took their lives inside their apartment in Neustrelitz, Germany – a small town about 90-minutes north of Berlin.

Now, that Tim knew what those fragile letters said, Jane pushed Tim to find out more. There had to be someone else alive, someone related to Mrs. Sebba.

So, Tim Mallad bought the premium package on Ancestry.com and went to work. But he kept running into dead ends with every click of the mouse.

One night, he finally identified someone – a man in Atlanta named Frank Pringham. He was a retired ad executive and turned out to be Helen Sebba’s grandson. That would also make Frank, Willy Weiss’ great uncle.

So, Tim made a cold call to Frank to tell him what he found in his grandmother’s old desk.

Suspicious at first, Frank admitted to Tim that he knew nothing about that side of his family.

Gradually, the two struck up a friendship with a mutual curiosity about the past and the Weiss’.

They dug through pictures, passports and paperwork to piece back together three lives lost more than 70-years earlier.

They got so overwhelmed in their quest for answers, that Tim and Frank decided they wanted to visit the small German town where the Weiss’ lived.

Returning to Germany, finding the mass grave NEUSTRELITZ, GERMANY

The apartment building where the Weiss’ lived still stands today. As a small town without a role in the Nazi’s military-industrial complex, Neustrelitz apparently went mostly unnoticed by Allied bombers during the war.

In the documentary, Tim and Frank find the apartment building where the Weiss’s lived – and died.

A current resident there allowed them inside to take a closer look. Our cameras descended the stairs with them, as well. The resident’s reaction to what happened to the Weiss’ in the place she now calls home made for an interesting moment.

Then, in one of the most powerful scenes in the documentary, Neustrelitz’s town archive arranged a visit to the cemetery where the Weiss’ are buried. Tim and Frank locate the mass grave and the exact spot where the Weiss’ remains lie, alongside 700 townspeople who suffered the same fate at the end of the war.

“I discovered it was a widespread phenomenon that nobody talked about, and nobody knew about actually,” said Florian Huber, PhD.

The author studied the suicide epidemic in 1945 and wrote Promise Me You’ll Shoot Yourself, a direct quote from another German diary during that same period.

But if suicide was so widespread in Germany in the final weeks of the war, why do so few people know about it today?

That’s because of where it happened in Germany.

Neustrelitz and other small towns that experienced the same loss of humanity in 1945 are all in the northeast part of the country. That fell under Soviet control when the Allies split up Germany after the war. And Russians forbid anyone to discuss what soldiers did.

“I can’t think of any other setting in the modern age in Western Europe where so many thousands of people killed themselves out of hopelessness, our of despair,” said Dr. Christian Goeschel, an expert in Modern European History at the University of Manchester in northern England.

Along with Dr. Huber, Dr. Goeschel is one of only a handful of scholars to study the mass suicides in Germany in 1945.

Dr. Goeschel documented his findings in a book called Suicide in Nazi Germany. And some of the passages he wrote are difficult to imagine.

“Whole good churchgoing families took their lives, drown themselves, hanged themselves, slit their wrists or allowed themselves to be burned up inside their homes,” wrote Dr. Goeschel in his book.

If it weren’t for Tim Mallad and Frank Pringham, the Weiss family’s very existence might have been lost to the passage of time. ‘Let Us Die’ explores the suicide epidemic in 1945 and brings the story of Willy, Dora and Ulla back to life.

The three-year project that produced 'Let Us Die' DALLAS

‘LET US DIE’ was a three-year passion project of WFAA reporter Jason Whitely and former WFAA photojournalist Taylor Lumsden. They completed it in between other assignments throughout the pandemic.

This is the first feature-length documentary that Whitely and Lumsden have produced.

‘LET US DIE’ will premiere at the Dallas International Film Festival in October 2022. Following that showing, there will be a number of other limited screenings in North Texas and beyond before the work eventually finds a home across WFAA’s platforms.