If you're one of the many parents who has the soundtrack of Frozen playing on repeat in your head, you certainly know Elsa. And Anna. And probably Moana, Mulan, Ariel, Tiana, Belle and even Elena — to name a few.

Everything from Band-Aids, to bottled water, to training pants are plastered with their smiling faces.

"Princess culture," as it's been dubbed by psychologists, is inescapable among the preschool set and can leave parents royally confused. Should we be rescuing our tiny humans from the pretty, pretty princesses? Maybe, maybe not. (And by the way, good luck taking a Cinderella costume away from a 3-year-old and her friends.)

Some argue the princess obsession is harming girls. Peggy Orenstein, author of Cinderella Ate My Daughter: Dispatches from the Front Lines of the New Girlie-Girl Culture, says it contributes to the “self-objectification” and “self-sexualization” that many girls face during their teenage years.

She became interested in what she calls the “princess industrial complex” when she noticed her daughter drawn into the explosion of princess-related merchandise everywhere she turned.

The princess culture can lead you "to the next phase, which is what I call the Kardashianization of girlhood,” Orenstein said.

There is some science to back up the critics. A 2016 study found that girls who are into princess culture at age 4 tend to be more gender stereotyped at age 5.

"Girls who adhere strongly to female gender stereotypes tend to limit themselves in different ways," said lead author Sarah Coyne, an associate professor of family life at Brigham Young University. For example, "they tend to think that they can’t do well in math in or science," Coyne said.

A separate study published last month in the journal Science, found that girls as young as 6 could be led to believe that men were inherently more brilliant and talented than women.

The movies

Critics point to certain storylines: In Sleeping Beauty, Princess Aurora does little but slumber and wait for a prince to save her; in The Little Mermaid, Orenstein points out that Ariel is “a girl who actually gives up her voice for a man.” And while Belle of Beauty and the Beast may be independent and well-read, Orenstein is frightened by the message that "if you just are kind enough and wonderful enough to the beast he’ll become a prince."

But others, including Jerramy Fine, author of In Defense of the Princess: How Plastic Tiaras and Fairytale Dreams Can Inspire Smart, Strong Women, contend that Disney movies are actually "narratives of female power and heroism and assertion."

"Female empowerment is also the fundamental message of the princess," Fine said. In fact, attacks on princess culture could be harmful because it tells our daughters that "something that they perceive as girly is wrong, which will make them feel bad about being a girl."

Fine points to compassion, caring, nurturing, long-term planning, non-competitiveness, empathy and communication as positive characteristics consistently found in Disney princesses.

"The princess dream doesn’t exist just because Disney is selling it," Fine writes. "It’s actually an ancient archetype that girls subconsciously recognize and subconsciously crave. When our daughters dress in their princess regalia, they are not attempting to be sexual objects or resigning themselves to domestic passivity — they’re asserting an ancient feminine force."

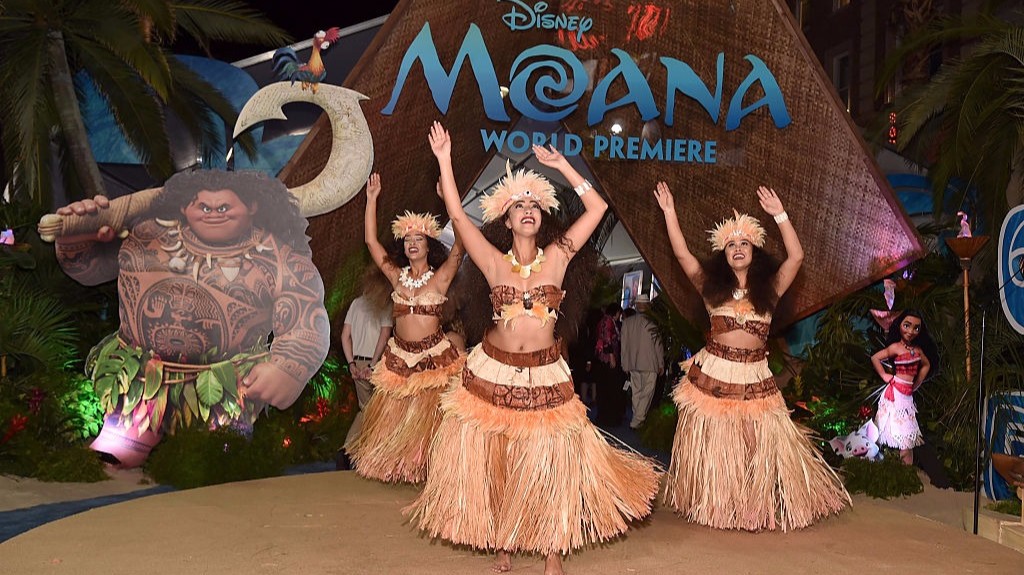

And in newer films, Disney female protagonists are increasingly strong, independent and diverse, with experts citing Moana, The Princess and the Frog, Frozen and Brave as some examples.

Recent characters even bristle at the princess label itself. For example, Moana defiantly declares she is not a princess in an exchange with the demi-god, Maui.

And, in the newly released Beauty and the Beast, a magical chest of drawers promises to dress Belle in "something worthy of a princess."

Belle replies, "I'm not a princess" and she goes with a pair of practical shoes.

Emma Watson, who Disney cast as Belle, is known for her feminist work as the founder of gender equality initiative HeForShe.

“We have talked to thousands of kids and parents around the world about the appeal of princesses and their feedback is consistent — they love the characters because of their wonderful stories and the focus on achieving your dreams. The emphasis on strong character qualities is purposeful and noticeable across the stories and the product,” a Disney spokesperson told USA TODAY.

The merch

There is, however, all the princess "stuff." Back in 2000, Disney launched the Disney Princess brand, which exploded into what Bloomberg calls a $5.5 billion enterprise. In the past, Disney had focused on promoting its movies, rather than characters. Now the company has licensed every conceivable product featuring its most beloved females characters.

And critics say the merchandise is heavily focused on appearance, with an abundance of beauty-themed products like makeup kits and dresses.

Coyne says "even when Disney gets it right in the movies" they "don’t quite get it right in the marketing and merchandise." She points to a makeover Merida from Brave got when she was crowned the 11th official Disney Princess.

"You take a really good character who is not very gender stereotyped," Coyne said, yet "when you look at the merchandise, they slim her down. They feminize her. They put makeup on her. They take her bow (and arrow) out."

Disney quickly dropped the madeover version of Merida from its website after a Change.org petition calling for a return to the original version got more than 200,000 signatures.

But not all Disney Princess products are about playing dress up. A "Dance Code Belle" doll tied to the release of the new, live-action version of Beauty and the Beast helps teach girls about computer coding. Last year, Disney launched its "Dream Big, Princess" campaign to "inspire girls and kids around the world to realize their full potential." One video posted on one of Disney's YouTube channels includes the caption "For every girl who dreams big, there’s a princess to show her it’s possible."

Even a critic like Orenstein admits her daughter owned her fair share of Disney princess toys and doesn't believe banishing the princess is a realistic solution.

"If you think that you’re going to offer your daughter broader ideas about what it means to be a girl by constantly saying no to her, you are delusional," she says.

So, what's a parent to do?

Here are some tips from the experts who spoke to USA TODAY:

- Limit, don't censor, the amount of princess movies your kids are watching. Disney itself offers plenty of alternatives like Inside Out and Zootopia.

- Give children a range of creative outlets. As a parent, you control the purse strings, so make sure your child has a variety of toys available.

- It's all about how you frame the discussion. Fine says playing princess "doesn’t have to be about just prancing around in a dress." She asks her daughter questions like, "What are you going to do to make your kingdom better today?" or "How are you helping people?"

- When it comes to body image, a mother has more influence than any movie or toy. Avoid complaining about your weight or stressing about diets and your appearance in front of your children.

- Let your kids know that beauty isn't only about appearance. Tell them they are beautiful because they shared a toy or did something kind.

- Consult the American Academy of Pediatrics' advice on media use among children. The group recommends giving kids ages 2 to 5 no more than one hour a day in front of a screen.

Coyne says the princess culture can be a "magical part of childhood" if parents are smart about it. Because it's Mom and Dad, not Belle or Elsa, who have the power to help their little girls live happily ever after.